Regression discontinuity I & II

- Slides

- Lecture videos

- R stuff

- Get data for example

- The effect of a gifted program on student test scores

- Step 1: Determine if process of assigning treatment is rule-based

- Step 2: Determine if the design is fuzzy or sharp

- Step 3: Check for discontinuity in running variable around cutpoint

- Step 4: Check for discontinuity in outcome across running variable

- Step 5: Measure the size of the effect

- Step 6: Compare all the effects

- Clearest and muddiest things

Lecture videos

Videos for each section of the lecture and the R demonstration are available at this YouTube playlist.

- Introduction

- Arbitrary cutoffs & causal inference

- Drawing lines & measuring gaps

- Main RDD concerns

- RDD with R

You can also watch the playlist (and skip around to different sections) here:

R stuff

Download all the R stuff you need to play along at home: week-11.zip. You can also open an RStudio.cloud project with everything ready to go.

Get data for example

Download this CSV file and put it in a folder named data in a new RStudio project:

The effect of a gifted program on student test scores

In this hypothetical example, students take a test in 6th grade to determine if they can participate in an academically and intellectually gifted (AIG) program during middle school and high school. In the AIG program students regularly get pulled out of their classes for extra work and lessons. At the end of high school, students take a final test (with a maximum of 100 points) to measure how much they learned overall. Remember, this is a hypothetical example and tests like this don’t really exist, but just go with it.

library(tidyverse) # For ggplot, %>%, and gang

library(broom) # For converting models into tables

library(rdrobust) # For robust nonparametric regression discontinuity

library(rddensity) # For nonparametric regression discontinuity density tests

library(wakefield) # Generate fake data

library(huxtable) # For side-by-side regression tables

# Fake program data

set.seed(1234)

aig_program <- r_data_frame(

n = 1000,

id,

test_score = rbeta(shape1 = 7, shape2 = 2),

final_score = rbeta(shape1 = 5, shape2 = 3),

race,

sex

) %>%

mutate(test_score = test_score * 100,

aig = test_score >= 75) %>%

mutate(final_score = final_score * 40 + 10 * aig + test_score / 2)Step 1: Determine if process of assigning treatment is rule-based

In order to join the AIG program, students have to score 75 points or more on the AIG test in 6th grade. Students who score less than 75 are not eligible for the program. Since we have a clear 75-point rule, we can assume that the process of participating in the AIG program is rule-based.

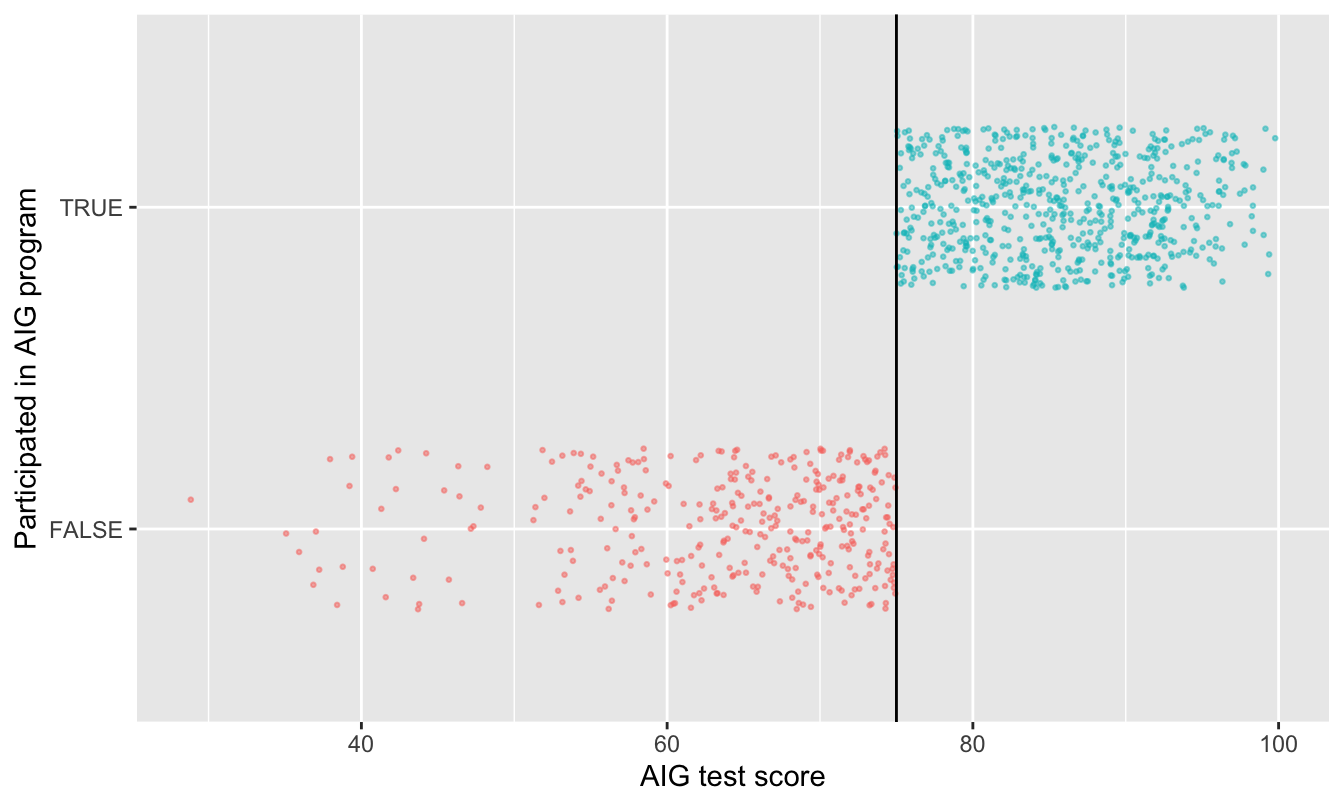

Step 2: Determine if the design is fuzzy or sharp

Since we know that the program was applied based on a rule, we want to next figure out how strictly the rule was applied. The threshold was 75 points on the test—did people who scored 73 slip into the AIG program, or did people who scored 80 not show up to the program? The easiest way to do this is with a graph, and we can get exact numbers with a table.

ggplot(aig_program, aes(x = test_score, y = aig, color = aig)) +

# Make points small and semi-transparent since there are lots of them

geom_point(size = 0.5, alpha = 0.5,

position = position_jitter(width = 0, height = 0.25, seed = 1234)) +

# Add vertical line

geom_vline(xintercept = 75) +

# Add labels

labs(x = "AIG test score", y = "Participated in AIG program") +

# Turn off the color legend, since it's redundant

guides(color = FALSE)

This looks pretty sharp—it doesn’t look like people who scored under 75 participated in the program. We can verify this with a table. There are no people where test_score is greater than 75 and aig is false, and no people where test_score is less than 75 and aig is true.

aig_program %>%

group_by(aig, test_score >= 75) %>%

summarize(count = n())## # A tibble: 2 x 3

## # Groups: aig [2]

## aig `test_score >= 75` count

## <lgl> <lgl> <int>

## 1 FALSE FALSE 346

## 2 TRUE TRUE 654This is thus a sharp design.

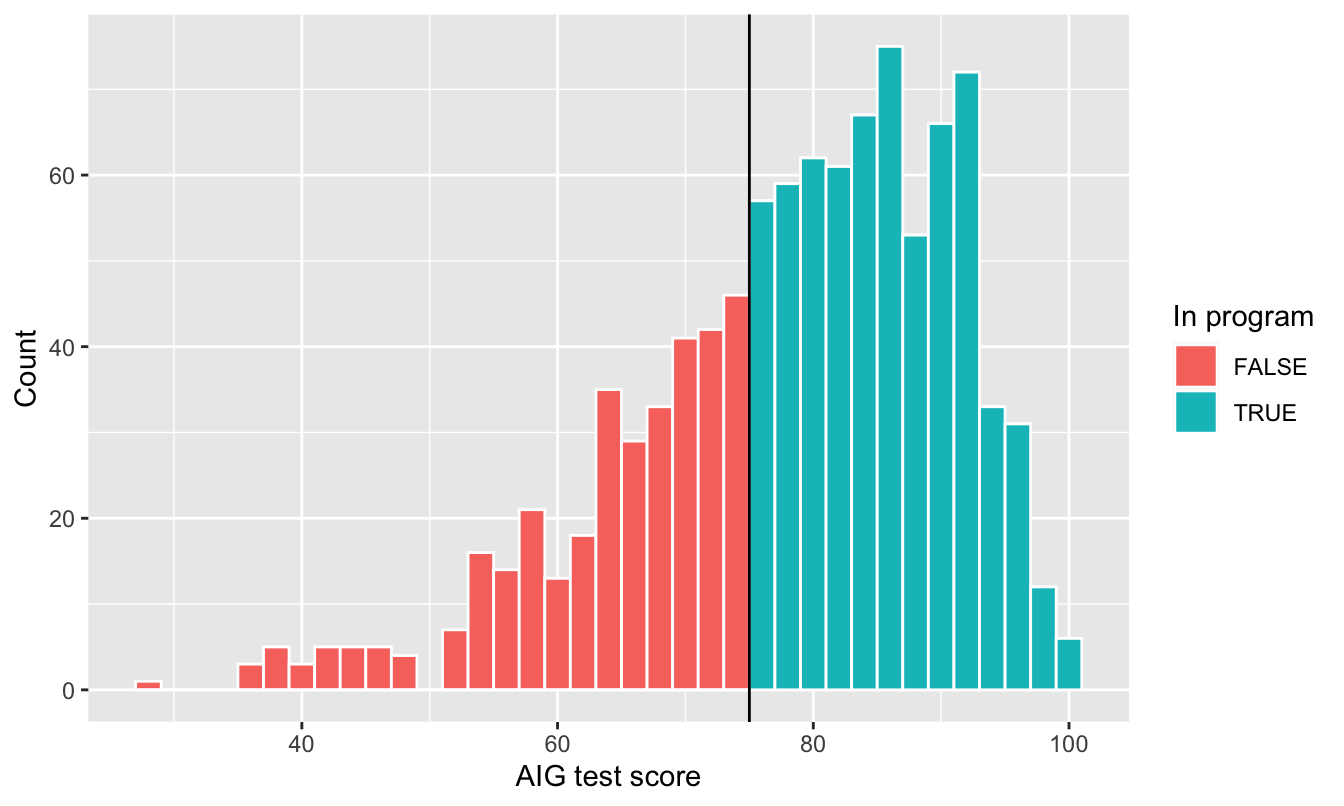

Step 3: Check for discontinuity in running variable around cutpoint

Next we need to see if there was any manipulation in the rating or running variable—maybe lots of people bunched up around 75 because of how the test was graded (i.e. teachers wanted to get students into the program so they bumped people up from 70 to 76). We can do this a couple different ways. First, make a histogram of the running variable (test scores) and see if there are any big jumps around the threshold:

ggplot(aig_program, aes(x = test_score, fill = aig)) +

geom_histogram(binwidth = 2, color = "white") +

geom_vline(xintercept = 75) +

labs(x = "AIG test score", y = "Count", fill = "In program")

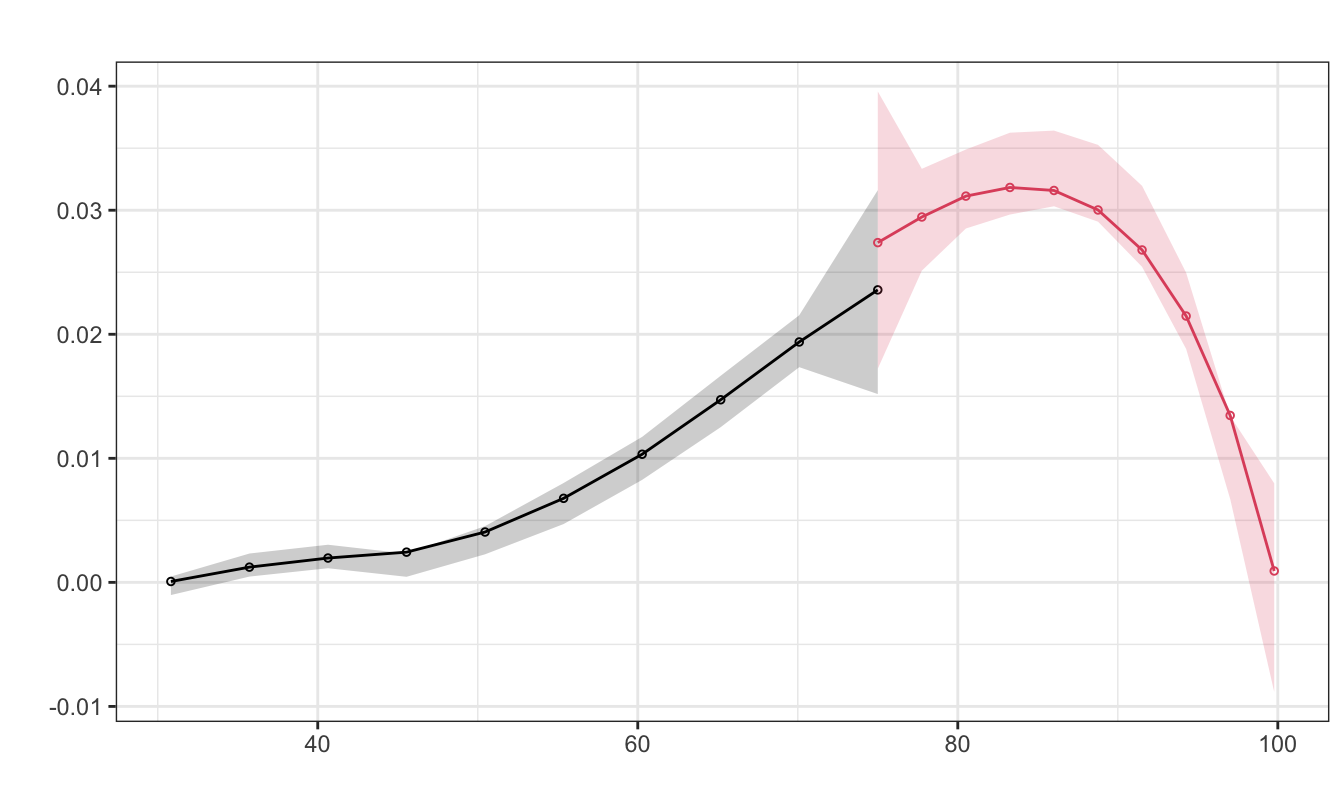

Here it looks like there might be a jump around the cutoff—there’s a visible difference between the height of the bars right before and right after the 75-point threshold. But is that difference statistically significant? To test that, we can do a McCrary density test (explained on pp. 185-86 of Causal Inference: The Mixtape). This puts data into bins like a histogram, and then plots the averages and confidence intervals of those bins. If the confidence intervals of the density lines don’t overlap, then there’s likely something systematically wrong with how the test was scored (i.e. too many people getting 76 vs 74). If the confidence intervals overlap, there’s not any significant difference around the threshold and we’re fine.

# The syntax for rdplotdensity is kinda wonky here. You have to specify rdd,

# which calculates the binned density of your running variable (and you have to

# give it the cutpoint as c = whatever), and then you have to specify x, which

# is the variable that goes on the x axis. In this case (and all cases?) it's

# the same variable, but this function makes you specify it twice for whatever

# reason. The type argument tells the plot to show both points and

# lines---without it, it'll only show lines

#

# Also, notice this aig_program$test_score syntax. This is one way for R to

# access columns in data frames---it means "use the test_score column in the

# aig_program data frame". The general syntax for it is data_frame$column_name

#

# Finally, notice how I assigned the output of rdplotdensity to a variable named

# test_density. In theory, this should make it show nothing---all the output

# should go to that object. Because of a bug in rdplotdensity, though, it will

# show a plot automatically even if assigning it to a variable. If we don't

# assign it to a variable you'll see two identical plots when knitting, which is

# annoying. So we save it as a variable to hide the ouput, but get the output

# for a single plot anyway. Ugh.

test_density <- rdplotdensity(rdd = rddensity(aig_program$test_score, c = 75),

X = aig_program$test_score,

type = "both") # This adds both points and lines

Based on this plot, there’s no significant difference in the distribution of test scores around the cutpoint. We’re good.

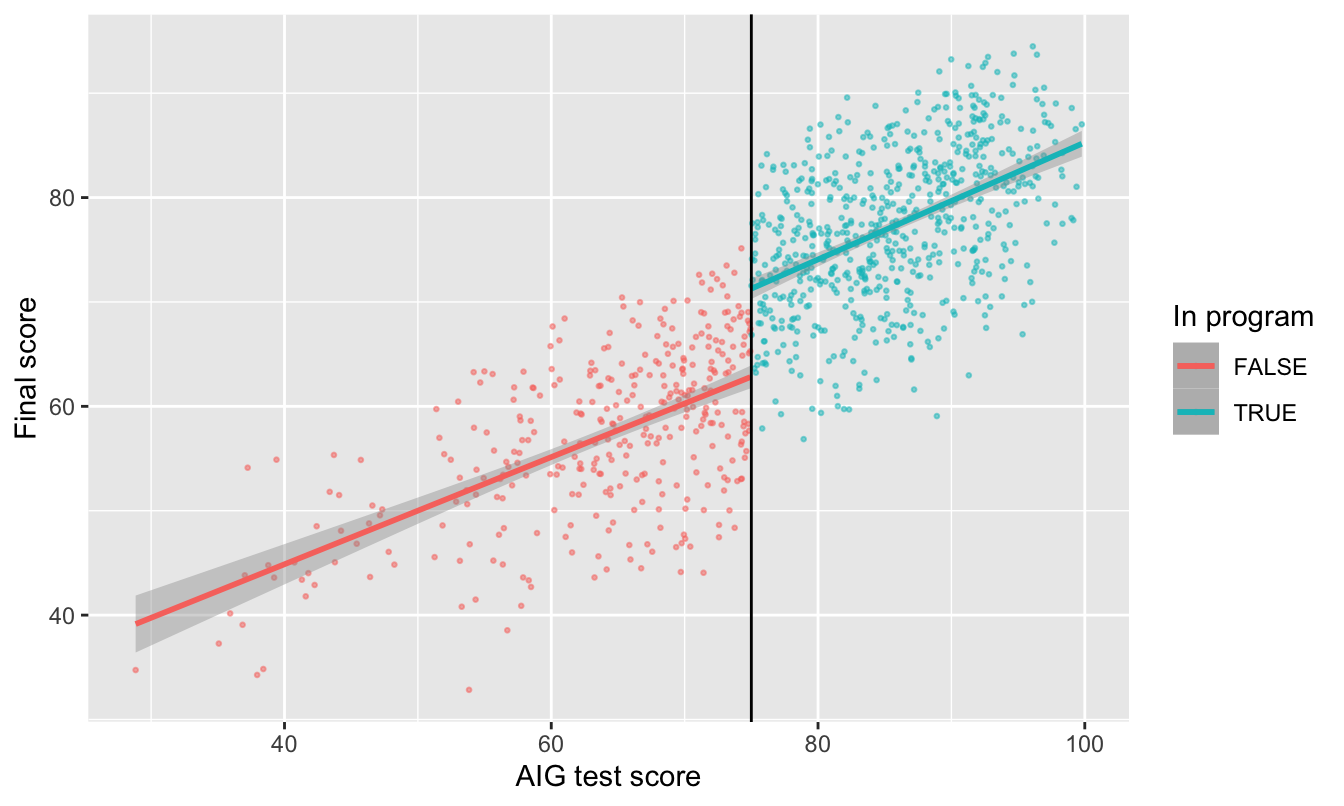

Step 4: Check for discontinuity in outcome across running variable

Now that we know this is a sharp design and that there’s no bunching of test scores around the 75-point threshold, we can finally see if there’s a discontinuity in final scores based on participation in the AIG program. Plot the running variable on the x-axis, the outcome variable on the y-axis, and color the points by whether they participated in the program.

ggplot(aig_program, aes(x = test_score, y = final_score, color = aig)) +

geom_point(size = 0.5, alpha = 0.5) +

# Add a line based on a linear model for the people scoring less than 75

geom_smooth(data = filter(aig_program, test_score < 75), method = "lm") +

# Add a line based on a linear model for the people scoring 75 or more

geom_smooth(data = filter(aig_program, test_score >= 75), method = "lm") +

geom_vline(xintercept = 75) +

labs(x = "AIG test score", y = "Final score", color = "In program")

Based on this graph, there’s a clear discontinuity! It looks like participation in the AIG program boosted final test scores.

Step 5: Measure the size of the effect

There’s a discontinuity, but how big is it? And is it statistically significant?

We can check the size two different ways: parametrically (i.e. using lm() with specific parameters and coefficients), and nonparametrically (i.e. not using lm() or any kind of straight line and instead drawing lines that fit the data more precisely). We’ll do it both ways.

Parametric estimation

First we’ll do it parametrically by using linear regression. Here we want to explain the variation in final scores based on the AIG test score and participation in the program:

\[ \text{Final score} = \beta_0 + \beta_1 \text{AIG test score} + \beta_2 \text{AIG program} + \epsilon \]

To make it easier to interpret coefficients, we can center the test score column so that instead of showing the actual test score, it shows how many points above or below 75 the student scored.

aig_program_centered <- aig_program %>%

mutate(test_score_centered = test_score - 75)

model_simple <- lm(final_score ~ test_score_centered + aig,

data = aig_program_centered)

tidy(model_simple)| term | estimate | std.error | statistic | p.value |

| (Intercept) | 63.1 | 0.466 | 135 | 0 |

| test_score_centered | 0.535 | 0.0278 | 19.2 | 2.09e-70 |

| aigTRUE | 8.47 | 0.743 | 11.4 | 2.27e-28 |

Here’s what these coefficients mean:

- \(\beta_0\): This is the intercept. Because we centered test scores, it shows the average final score at the 75-point threshold. People who scored 74.99 points on the AIG test score an average of 63 points on the final test.

- \(\beta_1\): This is the coefficient for

test_score_centered. For every point above 75 that people score on the AIG test, they score 0.53 points higher on the final test. - \(\beta_2\): This is the coefficient for AIG, and this is the one we care about the most. This is the shift in intercept when

aigis true, or the difference between scores at the threshold. Being in the AIG program increases final scores by 8.47 points.

One advantage to using a parametric approach is that you can include other covariates like demographics. You can also use polynomial regression and include terms like test_score² or test_score³ or even test_score⁴ to make the line fit the data as close as possible.

Here we fit the model to the entire data, but in real life, we care most about the observations right around the threshold. Scores that are super high or super low shouldn’t really influence our effect size, since we only care about the people who score just barely under and just barely over 75.

We can fit the same model but restrict it to people within a smaller window, or bandwidth, like ±10 points, or ±5 points:

model_bw_10 <- lm(final_score ~ test_score_centered + aig,

data = filter(aig_program_centered,

test_score_centered >= -10 & test_score_centered <= 10))

tidy(model_bw_10)| term | estimate | std.error | statistic | p.value |

| (Intercept) | 62.5 | 0.669 | 93.5 | 2.9e-316 |

| test_score_centered | 0.458 | 0.103 | 4.43 | 1.17e-05 |

| aigTRUE | 9.2 | 1.17 | 7.89 | 1.97e-14 |

model_bw_5 <- lm(final_score ~ test_score_centered + aig,

data = filter(aig_program_centered,

test_score_centered >= -5 & test_score_centered <= 5))

tidy(model_bw_5)| term | estimate | std.error | statistic | p.value |

| (Intercept) | 63.6 | 0.908 | 70.1 | 3.69e-168 |

| test_score_centered | 0.859 | 0.274 | 3.14 | 0.00191 |

| aigTRUE | 7.36 | 1.58 | 4.66 | 5.22e-06 |

We can compare all these models simultaneously with huxreg():

# Notice how I used a named list to add column names for the models

huxreg(list("Simple" = model_simple,

"Bandwidth = 10" = model_bw_10,

"Bandwidth = 5" = model_bw_5))| Simple | Bandwidth = 10 | Bandwidth = 5 | |

| (Intercept) | 63.075 *** | 62.513 *** | 63.614 *** |

| (0.466) | (0.669) | (0.908) | |

| test_score_centered | 0.535 *** | 0.458 *** | 0.859 ** |

| (0.028) | (0.103) | (0.274) | |

| aigTRUE | 8.470 *** | 9.196 *** | 7.361 *** |

| (0.743) | (1.166) | (1.581) | |

| N | 1000 | 497 | 257 |

| R2 | 0.716 | 0.513 | 0.456 |

| logLik | -3292.006 | -1640.572 | -842.102 |

| AIC | 6592.012 | 3289.145 | 1692.204 |

| *** p < 0.001; ** p < 0.01; * p < 0.05. | |||

The effect of aig differs a lot across these different models, from 7.3 to 9.2. Which one is right? I don’t know. Also notice how much the sample size (N) changes across the models. As you narrow the bandwidth, you look at fewer and fewer observations.

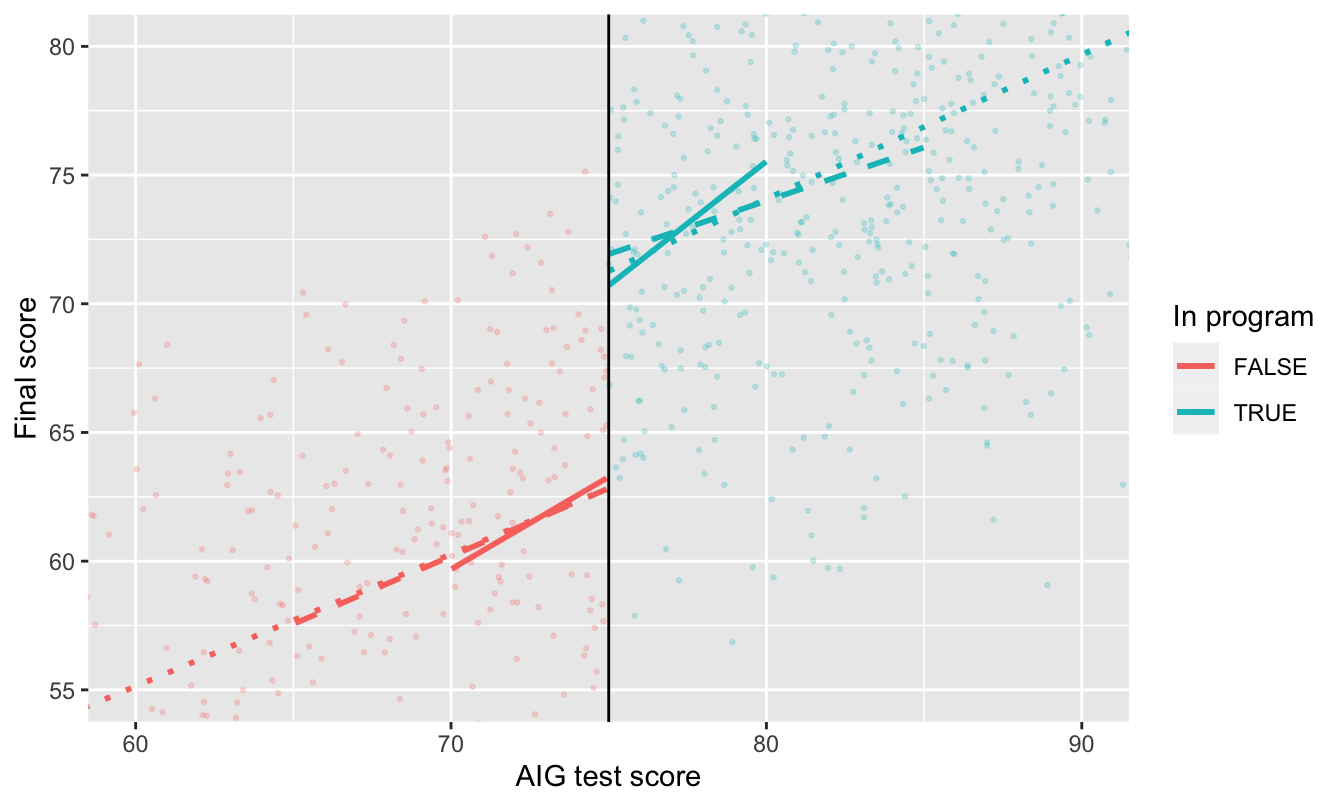

ggplot(aig_program, aes(x = test_score, y = final_score, color = aig)) +

geom_point(size = 0.5, alpha = 0.2) +

# Add lines for the full model (model_simple)

geom_smooth(data = filter(aig_program, test_score < 75),

method = "lm", se = FALSE, linetype = "dotted") +

geom_smooth(data = filter(aig_program, test_score >= 75),

method = "lm", se = FALSE, linetype = "dotted") +

# Add lines for bandwidth = 10

geom_smooth(data = filter(aig_program, test_score < 75, test_score >= 65),

method = "lm", se = FALSE, linetype = "dashed") +

geom_smooth(data = filter(aig_program, test_score >= 75, test_score <= 85),

method = "lm", se = FALSE, linetype = "dashed") +

# Add lines for bandwidth = 5

geom_smooth(data = filter(aig_program, test_score < 75, test_score >= 70),

method = "lm", se = FALSE) +

geom_smooth(data = filter(aig_program, test_score >= 75, test_score <= 80),

method = "lm", se = FALSE) +

geom_vline(xintercept = 75) +

# Zoom in

coord_cartesian(xlim = c(60, 90), ylim = c(55, 80)) +

labs(x = "AIG test score", y = "Final score", color = "In program")

Nonparametric estimation

Instead of using linear regression to measure the size of the discontinuity, we can use nonparametric methods. Essentially this means that R will not try to fit a straight line to the data—instead it’ll curve around the points and try to fit everything as smoothly as possible.

The rdrobust() function makes it really easy to measure the gap at the cutoff with nonparametric estimation. Here’s the simplest version:

# Notice how we have to use the aig_program$final_score syntax here. Also make

# sure you set the cutoff with c

rdrobust(y = aig_program$final_score, x = aig_program$test_score, c = 75) %>%

summary()## Call: rdrobust

##

## Number of Obs. 1000

## BW type mserd

## Kernel Triangular

## VCE method NN

##

## Number of Obs. 346 654

## Eff. Number of Obs. 138 198

## Order est. (p) 1 1

## Order bias (q) 2 2

## BW est. (h) 6.584 6.584

## BW bias (b) 9.576 9.576

## rho (h/b) 0.688 0.688

## Unique Obs. 346 654

##

## =============================================================================

## Method Coef. Std. Err. z P>|z| [ 95% C.I. ]

## =============================================================================

## Conventional 8.011 1.494 5.360 0.000 [5.082 , 10.940]

## Robust - - 4.437 0.000 [4.315 , 11.144]

## =============================================================================There are a few important pieces of information to look at in this output:

- The thing you care about the most is the actual effect size. This is the coefficient in the table at the bottom, indicated with the “Conventional” method. Here it’s 8.011, which means the AIG program causes an 8-point increase in final test scores. The table at the bottom also includes standard errors, p-values, and confidence intervals for the coefficient, both normal estimates (conventional) and robust estimates (robust). According to both types of estimates, this 8 point bump is statistically significant (p < 0.001; the 95% confidence interval definitely doesn’t ever include 0).

- The model used a bandwidth of 6.584 (

BW est. (h)in the output), which means it only looked at people with test scores of 75 ± 6.6. It decided on this bandwidth automatically, but you can change it to whatever you want. - The model used a triangular kernel. This is the most esoteric part of the model—the kernel decides how much weight to give to observations around the cutoff. Test scores like 74.99 or 75.01 are extremely close to 75, so they get the most weight. Scores like 73 or 77 are a little further away so they matter less. Scores like 69 or 81 matter even less, so they get even less weight. You can use different kernels too, and Wikipedia has a nice graphic showing the shapes of these different kernels and how they give different weights to observations at different distances.

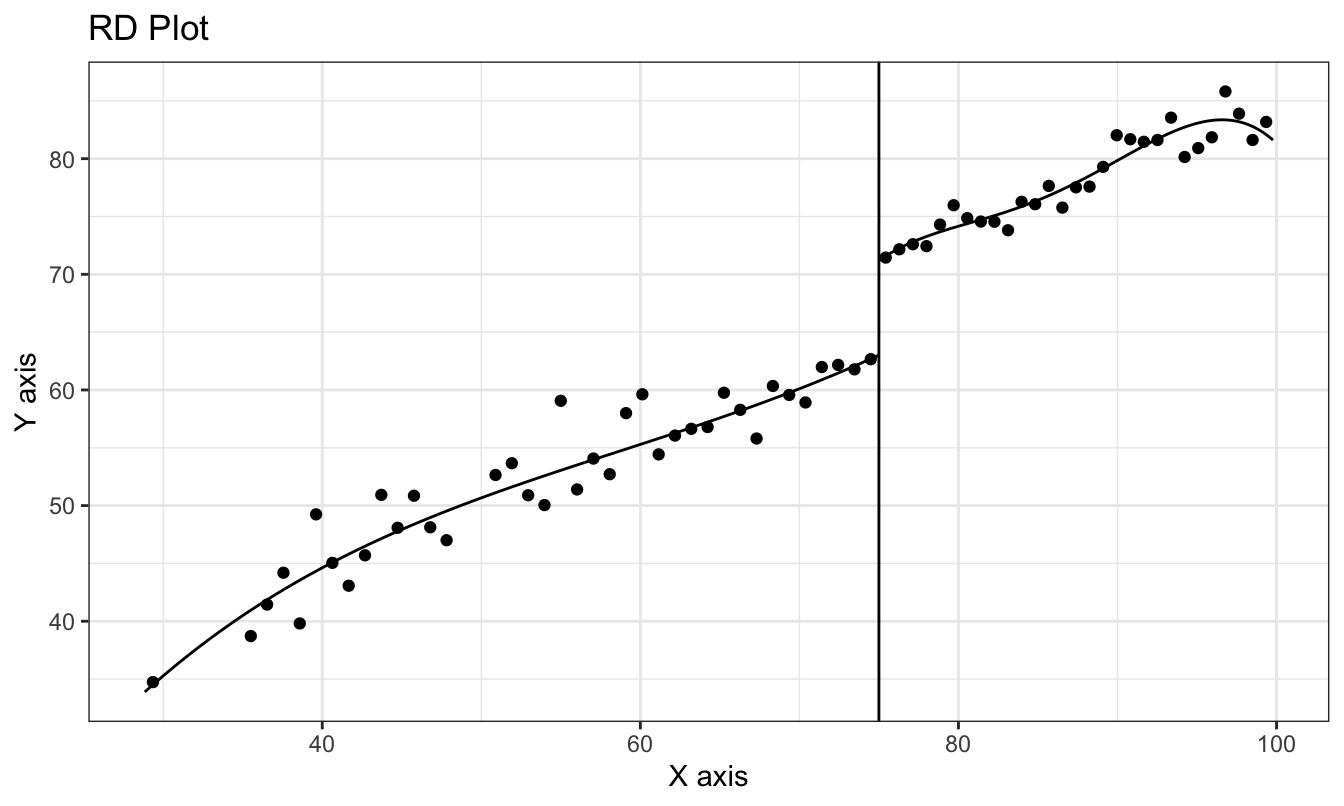

We can plot this nonparametric model with rdplot(). It unfortunately doesn’t use the same plotting system as ggplot(), so you can’t add layers like labs() or geom_point() or anything else, which is sad. Oh well.

rdplot(y = aig_program$final_score, x = aig_program$test_score, c = 75)

Look at that 8 point jump at 75! Neat!

By default, rdrobust() chooses the bandwidth size automatically based on fancy algorithms that economists have developed. You can use rdbwselect() to see what that bandwidth is, and if you include the all = TRUE argument, you can see a bunch of different potential bandwidths based on a bunch of different algorithms:

# This says to use the mserd version, which according to the help file for

# rdbwselect means "the mean squared error-optimal bandwidth selector for RD

# treatment effects". Sounds great.

rdbwselect(y = aig_program$final_score, x = aig_program$test_score, c = 75) %>%

summary()## Call: rdbwselect

##

## Number of Obs. 1000

## BW type mserd

## Kernel Triangular

## VCE method NN

##

## Number of Obs. 346 654

## Order est. (p) 1 1

## Order bias (q) 2 2

## Unique Obs. 346 654

##

## =======================================================

## BW est. (h) BW bias (b)

## Left of c Right of c Left of c Right of c

## =======================================================

## mserd 6.584 6.584 9.576 9.576

## =======================================================What are the different possible bandwidths we could use?

rdbwselect(y = aig_program$final_score, x = aig_program$test_score, c = 75, all = TRUE) %>%

summary()## Call: rdbwselect

##

## Number of Obs. 1000

## BW type All

## Kernel Triangular

## VCE method NN

##

## Number of Obs. 346 654

## Order est. (p) 1 1

## Order bias (q) 2 2

## Unique Obs. 346 654

##

## =======================================================

## BW est. (h) BW bias (b)

## Left of c Right of c Left of c Right of c

## =======================================================

## mserd 6.584 6.584 9.576 9.576

## msetwo 14.057 5.671 22.401 8.491

## msesum 6.039 6.039 8.939 8.939

## msecomb1 6.039 6.039 8.939 8.939

## msecomb2 6.584 6.039 9.576 8.939

## cerrd 4.661 4.661 9.576 9.576

## certwo 9.952 4.015 22.401 8.491

## cersum 4.275 4.275 8.939 8.939

## cercomb1 4.275 4.275 8.939 8.939

## cercomb2 4.661 4.275 9.576 8.939

## =======================================================Phew. There are a lot here. The best one was mserd, or ±6.5. Some say ±6, others ±4.5ish, other are asymmetric and say -14 before and +5 after, or -9 before and +4 after. Try a bunch of different bandwidths as part of your sensitivity analysis and see if your effect size changes substantially as a result.

Another common approach to sensitivity analysis is to use the ideal bandwidth, twice the ideal, and half the ideal (so in our case 6.5, 13, and 3.25) and see if the estimate changes substantially. Use the h argument to specify your own bandwidth

rdrobust(y = aig_program$final_score, x = aig_program$test_score, c = 75, h = 6.5) %>%

summary()## Call: rdrobust

##

## Number of Obs. 1000

## BW type Manual

## Kernel Triangular

## VCE method NN

##

## Number of Obs. 346 654

## Eff. Number of Obs. 136 197

## Order est. (p) 1 1

## Order bias (q) 2 2

## BW est. (h) 6.500 6.500

## BW bias (b) 6.500 6.500

## rho (h/b) 1.000 1.000

## Unique Obs. 346 654

##

## =============================================================================

## Method Coef. Std. Err. z P>|z| [ 95% C.I. ]

## =============================================================================

## Conventional 7.986 1.501 5.321 0.000 [5.044 , 10.928]

## Robust - - 4.492 0.000 [4.734 , 12.063]

## =============================================================================rdrobust(y = aig_program$final_score, x = aig_program$test_score, c = 75, h = 6.5 * 2) %>%

summary()## Call: rdrobust

##

## Number of Obs. 1000

## BW type Manual

## Kernel Triangular

## VCE method NN

##

## Number of Obs. 346 654

## Eff. Number of Obs. 237 409

## Order est. (p) 1 1

## Order bias (q) 2 2

## BW est. (h) 13.000 13.000

## BW bias (b) 13.000 13.000

## rho (h/b) 1.000 1.000

## Unique Obs. 346 654

##

## =============================================================================

## Method Coef. Std. Err. z P>|z| [ 95% C.I. ]

## =============================================================================

## Conventional 8.774 1.131 7.759 0.000 [6.558 , 10.991]

## Robust - - 5.182 0.000 [5.047 , 11.186]

## =============================================================================rdrobust(y = aig_program$final_score, x = aig_program$test_score, c = 75, h = 6.5 / 2) %>%

summary()## Call: rdrobust

##

## Number of Obs. 1000

## BW type Manual

## Kernel Triangular

## VCE method NN

##

## Number of Obs. 346 654

## Eff. Number of Obs. 74 95

## Order est. (p) 1 1

## Order bias (q) 2 2

## BW est. (h) 3.250 3.250

## BW bias (b) 3.250 3.250

## rho (h/b) 1.000 1.000

## Unique Obs. 346 654

##

## =============================================================================

## Method Coef. Std. Err. z P>|z| [ 95% C.I. ]

## =============================================================================

## Conventional 8.169 1.774 4.606 0.000 [4.693 , 11.645]

## Robust - - 3.433 0.001 [3.311 , 12.123]

## =============================================================================Here the coefficients change slightly:

| Bandwidth | Effect size |

|---|---|

| 6.5 (ideal) | 7.986 |

| 13 (twice) | 8.774 |

| 3.25 (half) | 8.169 |

You can also adjust the kernel. By default rd_robust uses a triangular kernel (more distant observations have less weight linearly), but you can switch it to Epanechnikov (more distant observations have less weight following a curve) or uniform (more distant observations have the same weight as closer observations; this is unweighted).

# Non-parametric RD with different kernels

rdrobust(y = aig_program$final_score, x = aig_program$test_score,

c = 75, kernel = "triangular") %>%

summary() # Default## Call: rdrobust

##

## Number of Obs. 1000

## BW type mserd

## Kernel Triangular

## VCE method NN

##

## Number of Obs. 346 654

## Eff. Number of Obs. 138 198

## Order est. (p) 1 1

## Order bias (q) 2 2

## BW est. (h) 6.584 6.584

## BW bias (b) 9.576 9.576

## rho (h/b) 0.688 0.688

## Unique Obs. 346 654

##

## =============================================================================

## Method Coef. Std. Err. z P>|z| [ 95% C.I. ]

## =============================================================================

## Conventional 8.011 1.494 5.360 0.000 [5.082 , 10.940]

## Robust - - 4.437 0.000 [4.315 , 11.144]

## =============================================================================rdrobust(y = aig_program$final_score, x = aig_program$test_score,

c = 75, kernel = "epanechnikov") %>%

summary()## Call: rdrobust

##

## Number of Obs. 1000

## BW type mserd

## Kernel Epanechnikov

## VCE method NN

##

## Number of Obs. 346 654

## Eff. Number of Obs. 129 178

## Order est. (p) 1 1

## Order bias (q) 2 2

## BW est. (h) 5.994 5.994

## BW bias (b) 9.277 9.277

## rho (h/b) 0.646 0.646

## Unique Obs. 346 654

##

## =============================================================================

## Method Coef. Std. Err. z P>|z| [ 95% C.I. ]

## =============================================================================

## Conventional 7.866 1.547 5.084 0.000 [4.834 , 10.898]

## Robust - - 4.184 0.000 [4.012 , 11.082]

## =============================================================================rdrobust(y = aig_program$final_score, x = aig_program$test_score,

c = 75, kernel = "uniform") %>%

summary()## Call: rdrobust

##

## Number of Obs. 1000

## BW type mserd

## Kernel Uniform

## VCE method NN

##

## Number of Obs. 346 654

## Eff. Number of Obs. 121 163

## Order est. (p) 1 1

## Order bias (q) 2 2

## BW est. (h) 5.598 5.598

## BW bias (b) 10.148 10.148

## rho (h/b) 0.552 0.552

## Unique Obs. 346 654

##

## =============================================================================

## Method Coef. Std. Err. z P>|z| [ 95% C.I. ]

## =============================================================================

## Conventional 7.733 1.554 4.975 0.000 [4.686 , 10.779]

## Robust - - 4.081 0.000 [3.776 , 10.753]

## =============================================================================Again, the coefficients change slightly:

| Kernel | Effect size |

|---|---|

| Triangular | 8.011 |

| Epanechnikov | 7.866 |

| Uniform | 7.733 |

Which one is best? ¯\_(ツ)_/¯. All that really matters is that the size and direction of the effect doesn’t change. It’s still positive and it’s still in the 7-8 point range.

Step 6: Compare all the effects

We just estimated a ton of effect sizes. In real life you’d generally just report one of these as your final effect, but you’d run the different parametric and nonparametric models to check how reliable and robust your findings are. Here’s everything we just found:

| Method | Bandwidth | Kernel | Estimate |

|---|---|---|---|

| Parametric | Full data | Unweighted | 8.470 |

| Parametric | 10 | Unweighted | 9.196 |

| Parametric | 5 | Unweighted | 7.361 |

| Nonparametric | 6.584 | Triangular | 8.011 |

| Nonparametric | 6.5 | Triangular | 7.986 |

| Nonparametric | 13 | Triangular | 8.774 |

| Nonparametric | 3.25 | Triangular | 8.169 |

| Nonparametric | 6.584 | Epanechnikov | 7.866 |

| Nonparametric | 6.584 | Uniform (unweighted) | 7.733 |

In real life, I’d likely report the simplest one (row 4: nonparametric, automatic bandwidth, triangular kernel), but knowing how much the effect varies across model specifications is helpful.

Clearest and muddiest things

Go to this form and answer these three questions:

- What was the muddiest thing from class today? What are you still wondering about?

- What was the clearest thing from class today?

- What was the most exciting thing you learned?

I’ll compile the questions and send out answers after class.